We spend this episode looking at what happened after women got the vote. If you missed Part 1, check it out — we looked at the long years leading up to 1920. But in Part 2, we take you on a journey through history, from the Roaring Twenties through the Great Depression, through the Civil Rights Era, to Women’s Lib in the ’60s and ’70s, all the way up to the early 2000s. Suffrage didn’t change everything overnight…it was more like a slow burn. Our guests include Susan Ware, a historian focused on feminism; Gina Luria Walker, professor of Women’s Studies at the New School in New York, and Nell Merlino, creator of Take Your Daughters to Work Day with Gloria Steinem at the Ms. Foundation.

Check out the entire 100 Years of Power project to learn more about women’s history, like you’ve never heard it.

More in this series

100 Years of Power, Part 1: Battle for Suffrage

How Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton led a rancorous fight, at times at odds with Lucy Stone and Sojourner Truth. With historian Ellen DuBois.

100 Years of Power, Part 3: What the Future Holds

In 2020, six diverse women run for president, and Nancy Pelosi takes the House. With experts Molly Ball, Kelly Dittmar, Ronnee Schreiber and Glynda Carr.

MUSIC: Madame Gandhi, “The Future is Female”

SUE: You're listening to 100 Years of Power...

VARIOUS VOICES: ...100 Years of Power...

COLLEEN: You're listening to 100 Years of Power from The Story Exchange, where we look to history to understand how far women have come —

SUE: — and how far we still need to go.

COLLEEN: I'm Colleen DeBaise.

SUE: And I'm Sue Williams.

COLLEEN: So let's set the scene...it's the morning of August 19, 1920, and let's pretend I haven't left home in a while. I haven't seen anyone...actually, this sort of sounds like my life these past few months!

SUE: It sounds like mine too! So it's not hard to imagine this at all...

MUSIC: 1920s band music playing

COLLEEN: So I pick up my morning newspapers — the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal...Now, if something momentous had happened, I'd expect banner headlines, sort of like a few years earlier, when the Titanic sank and the coverage took up the ENTIRE PAGE.

SUE: So the papers on August 19, 1920 — that's the day after the 19th Amendment was ratified, giving 22 million American —

COLLEEN: 22 million!

SUE: — 22 million women the right to vote. It was the culmination of a decades-long battle led by some of the most famous women in our history — Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton...

PROTESTERS SOT: (chanting) We want the vote! We want the vote!

COLLEEN: Yep. Oh, there we go — I see it's on page 8 of the Wall Street Journal.

SUE: Page 8?

COLLEEN: Yep.

SUE: How about the New York Times?

COLLEEN: Well, it made the front page there — although a story about the Battle of Warsaw gets pretty much the same amount of play.

SUE: Unbelievable.

COLLEEN: What's evident in looking at the coverage — and our researcher Noël checked into how newsmen all over the country covered this story — instead of a celebratory tone, there seemed to be a lot of doubt that this “women's suffrage thing” would stick.

SUE: So this is perhaps a good segway into Part Two of our 100 Years of Power podcast.

COLLEEN: We're going to spend this episode looking at what happened after women got the vote.

SUE: If you missed Part One, check it out — we looked at the looong years leading up to 1920.

COLLEEN: Today, we’ll take you on a journey through history — the 1920s, through the Great Depression, to women’s lib in the 1970s, all the way up to the early 2000s. Stick around!

MUSIC: Madame Gandhi, “The Future is Female”

VICTORIA: Honestly, after talking to historians, realizing how hard these women fought for the vote...

COLLEEN: That's producer Victoria Flexner.

VICTORIA: ...it's kind of mind-blowing to think that the press covered it as if...as if it was just some minor event. An anomaly of political legislation that might not even go through.

SUSAN WARE: You know, in some ways it's discouraging that more hasn't changed.

VICTORIA: That’s Susan Ware.

WARE: I'm a historian, with a special focus on the history of feminism.

VICTORIA: Susan and I sat down to talk about what happened after 1920.

VICTORIA (FROM ZOOM): I hope you’re doing all right in these really strange, weird times!

WARE: Strange and weird!

COLLEEN: And what you'll hear might seem...anti-climatic.

VICTORIA: Not a lot happened for women immediately after 1920, except perhaps the 1921 Sheppard-Towner Act...

COLLEEN: ...which provided federal funding for maternal and child care...

VICTORIA: ...and then the Cable Act of 1922...

COLLEEN: ...which ensured a woman would not lose her citizenship, and therefore her right to vote, if she married a foreigner.

WARE: There really weren’t that many specific laws that were passed that one could say were directly because women voters demanded them.

VICTORIA (FROM ZOOM): Do you think perhaps it's a fair statement to say that women had to learn how to become politically active?

WARE: I would turn that around and say, again, harking back to suffrage, how political they actually were without the vote. And they were able to mobilize through voluntary organizations, through their own groups like temperance and suffrage, and they really made a difference.

VICTORIA: And let's not forget, during the final push, suffragists even had to grapple with the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic.

COLLEEN: Rallies and speeches were cancelled...

VICTORIA: ...but they still got it done.

MUSIC: Madame Gandhi, “The Future is Female”

VICTORIA: So after 1920...

WARE: ...American women need to learn how to be effective voters, which is different than being political.

VICTORIA (FROM ZOOM): Interesting.

WARE: Men also had to learn about how, effectively, to deal with the new women voters. I think there's a learning curve for both men and women in public life in the 1920s and '30s.

VICTORIA: I asked Susan to explain the difference between voting behavior and being a politically active citizen.

WARE: Well, I vote once every two years or so, but I'm much more politically active than that — supporting organizations and reaching out to politicians as a constituent, and a whole range of political behavior.

VICTORIA: When Susan said this, it really made me stop and think.

COLLEEN: How so?

VICTORIA: Well, we’ve been so laser-focused on voting, on suffrage, on the concept of voting as a means through which women could improve their lives. But Susan’s right — being politically active is about so much more than just voting.

COLLEEN: Mm. So one might argue that — after suffrage — women now are freed up to mobilize behind other issues.

VICTORIA: That's right. And here we start to see one very famous woman leader emerge, not just on the national stage but also on the world stage.

MUSIC: Happy days are here again, the skies above are clear again...

ELEANOR ROOSEVELT: Franklin and I had a desire to see improvements for people.

WARE: By 1932 there is a political realignment that has been going on that deposits a Democratic president in the White House, Franklin Roosevelt, who just happens to have one of the most activist and important wives as part of his team, Eleanor Roosevelt. She really helps to facilitate the entry of women into high echelons of government power.

ELEANOR ROOSEVELT: I knew about social conditions, perhaps more than he did. But he knew about government and how you could use government to improve certain things. And I think we began to get an understanding of teamwork.

VICTORIA: The Roosevelts moved into the White House in 1933.

FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT: But the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.

WARE: You have this terrible depression, unprecedented, and a government — a federal government and state governments that decide that they need to take unprecedented action.

VICTORIA: FDR's plan, of course, is called the New Deal.

COLLEEN: One program that comes out of it is Social Security.

VICTORIA: And while FDR is generally credited as the architect of the New Deal, there were a huge number of people who worked on it behind the scenes — including Eleanor, of course.

COLLEEN: And I just want to pause for a second here to talk about this time period, and what’s going on with women in general. Even though it’s the Depression, it’s also Hollywood’s Golden Age, as people turn to movies and music for escape. We see the emergence of female artists who are still legends today. There’s sex symbols like Mae West, of course...

MAE WEST: Well, when I’m good I’m very good. But when I’m bad, I’m better.

VICTORIA: But there’s also stars like Katharine Hepburn who actually display a kind of feisty independence that might be reflective of women’s new assertiveness.

COLLEEN: This is from the 1933 movie Morning Glory, where she plays an aspiring actress.

KATHARINE HEPBURN: You know, from now on, I’m accepting no part unless I feel that I’m particularly fitted for it.

COLLEEN: That same year, we have jazz singer Billie Holiday cutting her first hit.

BILLIE HOLIDAY MUSIC: I jumped out of the frying pan, and right into the fire...

VICTORIA: And of course in the 1940s, we’ll see women stepping into a whole new set of roles, as they became involved in the war effort. But back to FDR and the New Deal.

COLLEEN: So, were there other women involved besides Eleanor?

VICTORIA: In fact, yes...

WARE: ...Frances Perkins, the first woman to serve in the cabinet, as Secretary of Labor. Now, she's someone that both Roosevelts have known from the end of the suffrage movement.

VICTORIA: There was also Molly Dewson...

WARE: ...a social worker turned political boss.

VICTORIA: And there was Hilda Worthington Smith, who became FDR’s education specialist.

VICTORIA (FROM ZOOM): In your book Beyond Suffrage: Women in the New Deal, you write about how the New Deal administration of Franklin Roosevelt offered “unprecedented access to power to a talented group of women who flocked to Washington in the 1930s.” Why do you think the environment in Washington in the 1930s was right for women?

WARE: A lot of the reasons why this women's network was able to work together so cohesively was that they had been working together in New York State already. They knew each other, they knew the Roosevelts, they knew how to get things done.

COLLEEN: So in part, Susan is saying that a lot of the political connections made during the suffrage movement, actually now began to pay off in D.C.?

VICTORIA: Basically, yeah. I mean, we know that a lot of politics is about connections and relationships. And though women might have been new to official political positions, they had been politic-ing since the mid-19th century.

WARE: And so because the expertise of many of these women was in the field of social welfare, they were the ones who knew how to put these programs together and how to administer them.

VICTORIA: This podcast is called “100 Years of Power,” but one thing I’ve learned in my reporting is that women had to carefully and quietly wield any newfound power, especially in the decades after suffrage passed. They were guiding the hands of men in power, rather than being in the limelight themselves.

WARE: There would often be a male head of, let's say, the Social Security Administration, and a female would be the assistant head or something. The women were quite happy to stay in the background, because to them it was just amazing that, here they were working at the highest levels of the federal government on causes that they had cared about. And also, I think they're probably savvy enough as feminists and as women to know that if they do start doing that, that there's going to be pushback from the men.

VICTORIA: Right, we’ve seen it before. Moments of great progress are always met with pushback.

WARE: Some of these pathbreaking early politicians in the 1920s and '30s, they really do have to be careful. And I would have hoped that here we are, 70 years later, that we weren't still having to tread so carefully, but everything anybody has noticed about gender — 2016, '18, what happened in 2020, it's still there.

MUSIC: Madame Gandhi, “The Future is Female”

COLLEEN: We’ll be back after a short break.

SUE: During our breaks, we’ve been asking women to share their first voting memories. Here’s Glynda Carr of New York City. Her parents gave her jewelry for her 18th birthday, but that’s not what she remembers most.

GLYNDA CARR: My mother put me in her car and drove me down to Town Hall and registered me to vote, right. And every election until the day she died, she would call my brothers and I like, “Did you vote?” And so that’s the tradition.

SUE: Glynda’s now the founder of Higher Heights, an organization dedicated to growing Black women’s political power.

COLLEEN: Welcome back. We've been talking about what happened after women won the vote.

VICTORIA: And we've titled this episode “Slow Burn,” because I think that's what best describes the situation.

COLLEEN: Right. While we like to think that suffrage was a momentous event for women —

VICTORIA: And it was!

COLLEEN: — it just didn't change everything overnight.

VICTORIA: And that's particularly the case for Black women.

WARE: We have to remember that for most Black women, unless they lived in northern cities, they were not able to vote until 1965 and the Voting Rights Act.

COLLEEN: While the 19th Amendment in theory granted universal female suffrage — it really only did so for white women.

VICTORIA: Yes, being able to vote really depended on the color of your skin and where you were geographically. Many Southern states forced Afrian Americans to take “voter literacy” tests that were confusing and almost impossible to pass.

COLLEEN: Some listeners might have seen the 2014 movie Selma, which is based on the 1965 Selma to Montgomery voting rights marches.

VICTORIA: There's a real-life character in the movie, Annie Lee Cooper, played by Oprah Winfrey, who was deterred from registering to vote.

COLLEEN: She famously fought back, when a white sheriff prodded and beat her with a billy club.

VICTORIA: Here's a short clip from CBS This Morning, of Oprah talking about why she was drawn to the role.

OPRAH WINFREY: All of those people, ancestors who are part of my legacy, our legacy, that keep getting up and kept trying — the fact that you go, and you’re denied, and then you go home and then you study the Constitution and you go again and you know that going, you could risk your life or have your house burn down?

MARTIN LUTHER KING JR: All the world today knows that we are here and we are standing before the forces of power in the state of Alabama, saying we ain’t gonna let nobody turn us around!

VICTORIA: The civil rights movement ushered in a new era, another small stepping stone towards equality.

COLLEEN: The landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 ended segregation, at least on paper.

VICTORIA: And the next year the Voting Rights Act prohibited racial discrimination in voting —

COLLEEN: — though we all know discrimination has not ended.

PROTESTERS SOT: (chanting) Black Lives Matter! Black Lives Matter! No justice, no peace! No justice, no peace!

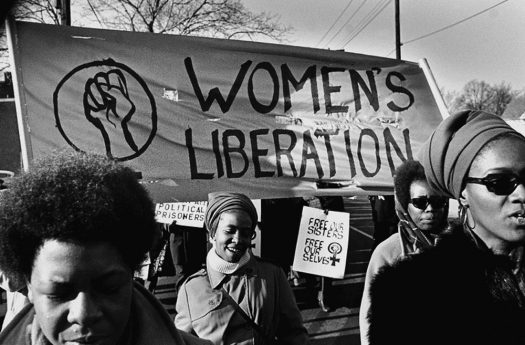

VICTORIA: The civil rights movement also coincided with a growing women’s movement —

COLLEEN: — popularly called women’s liberation, or just women's lib.

VICTORIA: The suffrage movement is often now referred to as “first-wave feminism,” while the women’s movement is what we would now call “second-wave feminism.”

COLLEEN: And who were the women leading this new movement? The Anthonys, Stantons and Stones of their day?

VICTORIA: Well, just as Elizabeth Cady Stanton had that revelation in 1848 one day at afternoon tea, pouring out “the torrent” of her “long-accumulating discontent,” a woman named Betty Friedan did something similar when she published her 1963 book The Feminine Mystique.

COLLEEN: Ah. The Feminine Mystique this was incredibly influential book.

VICTORIA: It was a total game changer. It was coming off the 1950s, when women had been taught to live in pursuit of marriage and motherhood, but they’d also been exposed to higher learning. And instead of being allowed to explore their own intellectual passions, they found themselves living lives dedicated to childrearing, casserole making and martini shaking.

COLLEEN: Well, one of those three doesn't sound too bad!

VICTORIA: Well, they were largely making the martinis for their husbands!

COLLEEN: Now I'm outraged! In all seriousness, this was when “housewifery” was repackaged as a career.

1950S COMMERCIAL ANNOUNCER: She’s got a man she’s promised to love, honor and...

1950S COMMERCIAL ACTRESS: Keep house for the right way!

1950S COMMERCIAL ACTOR: Does that mean I’ll never have to deal with the dishes?

1950S COMMERCIAL ACTRESS: Never!

VICTORIA: Exactly. And the frustration these women felt — well, Friedan called it so famously, “the problem that has no name.” She wrote of it...

ACTRESS AS BETTY FRIEDAN: “Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night — she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question — ‘Is this all?’”

VICTORIA: Friedan’s work woke up a generation of housewives, who, though they had been given the vote, were finding that this was not quite enough. And women like, say, Shirley Chisholm began to fight for something more.

SHIRLEY CHISHOLM: And my presence before you now symbolizes a new era in American political history.

COLLEEN: Shirely Chisholm became the first African American woman elected to Congress in 1968.

VICTORIA: During her time in Congress she served on the Education and Labor Committee, the Veteran’s Affairs Committee, The House Agriculture Committee...

COLLEEN: An odd appointment for a New York congresswoman representing Brooklyn.

VICTORIA: It was a slight for sure. But she turned it around and used her time there to expand the Food Stamps Program.

COLLEEN: That's a creative way to wield power. What happened after that?

VICTORIA: Well, in 1972 she ran for president — becoming the first black major party candidate, also making her the first woman in history to ever run for the Democratic party’s presidential nomination. She said of her candidacy...

SHIRLEY CHISHOLM: I am not the candidate of black America, although I am black and proud. I am not the candidate of the women's movement of this country, although I am a woman and I’m equally proud of that...I am the candidate of the people of America.

VICTORIA: As so many generations of women before her have learned —

COLLEEN: — and so many generations of women are still learning —

VICTORIA: — her time had not yet come. She later said of her candidacy, “I met more discrimination as a woman than for being black. Men are men.”

COLLEEN: So, let's review. We've talked about the New Deal, civil rights...now we're getting up to the 1970s.

VICTORIA: Drumroll...

COLLEEN: Let's talk about the Equal Rights Amendment.

VICTORIA: This was the cornerstone of the women’s movement, a proposed amendment to the Constitution designed to end unequal legal distinctions between men and women in terms of divorce, property, employment...

COLLEEN: And which member of the women’s movement wrote the ERA?

VICTORIA: None of them. It was actually written by Alice Paul!

COLLEEN: Wow, the suffragist?

VICTORIA: Yup, our first-wave feminist suffragist Alice Paul wrote the Equal Rights Amendment in 1923.

COLLEEN: Huh.

VICTORIA: But it wasn’t until the women’s movement picked up momentum in the ’60s that the ERA became this sort of touchstone piece of legislation designed to give true equality to men and women.

MARTHA GRIFFITHS: That is exactly what the Equal Rights Amendment would do.

VICTORIA: And that is the late Martha Griffiths, a Congresswoman from Michigan who re-introduced the bill in 1971, after it had floundered in legislative purgatory for 48 years. In this 1974 conversation with the U.S. Information Service she explains what the bill will do.

GRIFFITHS: What it will really do is to force governments, when they make a law or pass legislation or whatever they may do, to make it apply equally to both sexes. They can not discriminate on the basis of sex alone.

VICTORIA: Griffths goes on to say that the bill will be ratified, likely in 1975.

COLLEEN: But that didn't happen.

VICTORIA: Nope. Despite epic efforts by the National Organization of Women —

COLLEEN: — and support from iconic activists like Gloria Steinem —

VICTORIA: — there was a sizeable contingent of women fighting against the ERA...Enter Phyllis Schlafly: lawyer, author, and conservative activist extraordinaire.

COLLEEN: Here’s a clip from the public affairs show Firing Line in 1973.

PHYLLIS SCHLAFLY: We find as we look into the matter that ERA won’t give women anything which they haven’t already got or have a way of getting.

WARE: I mean, nobody can match Phyllis Schlafly. She knew how to get things done and she knew how to play the media, and can you imagine if she had been a man? I mean —

VICTORIA (FROM ZOOM): She would've been president.

WARE: Yes, I think she probably would've.

VICTORIA: She organized housewives across the nation to pressure their elected officials to vote against the ERA because she believed it would destroy the very core of what she believed female identity was.

COLLEEN: Some listeners might know her story from the new FX series Mrs. America, where she’s played by Cate Blanchett.

WARE: It's hard to know what really gets people motivated to be politically active and then to be good at it; and then what — why certain people end up going one route and other women end up going another route.

COLLEEN: It reminds me of the women who fought against suffrage.

VICTORIA: It does. And it's hard for me, as a person who did not grow up during these times, to understand why women throughout history wouldn't want equal rights.

GINA LAURIA WALKER: Because women are isolated, they are lonely, they know they are alone, and they're kind of scared of everything, including themselves and their shadows.

VICTORIA: That’s Gina Lauria Walker.

LAURIA WALKER: I'm professor of Women's Studies at the New School in New York.

VICTORIA: She’s also the director of The New Historia, an initiative committed to uncovering women of the past who produced knowledge...

LAURIA WALKER: ...and incorporating this new knowledge into literally a new history.

VICTORIA: Full disclosure, I studied with Professor Walker at The New School.

LAURIA WALKER: There are women who are determined to figure out how to move the collective of women forward, but that is so hard because women are so divided.

VICTORIA (FROM ZOOM): Yeah.

LAURIA WALKER: They're divided by all the things that divide men.

COLLEEN: Because women, as a group, are just as diverse; just as complicated.

VICTORIA: And ultimately Phyllis Schlafly and her followers defeated the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, arguing it would force women into combat, legalize gay marriage, abortion and destroy traditional gender roles. If we’re talking about how women in America have wielded power — well, this is one hell of an example. Schlafly proved women had political power, even if it’s not necessarily the kind progressive power that some had envisioned.

COLLEEN: Where does the ERA stand today?

VICTORIA: Well, states had until 1982 to ratify it — so that date has come and gone. But in recent years with the rise of Me Too and now fourth-wave feminism, there have been renewed efforts. Nevada ratified the ERA in 2017, and Virginia just a couple months ago in January..so I guess the fight continues.

COLLEEN: But even if the ERA did not pass, there were still specific grievances that could be addressed.

VICTORIA: Coming up, we cruise into the 1980s and the big bang in women's entrepreneurship.

COLLEEN: Stick around.

COMMERCIAL: The Story Exchange is a nonprofit media company that provides inspiration and information for women entrepreneurs. If you like what you’re hearing, check out Episode One, about Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, featuring historian Ellen DuBois. It’s Episode One: Battle for Suffrage.

COLLEN: Welcome back!

NELL MERLINO: We were still at that point in the ’80s, still proving that we could do this shit!

COLLEEN: That is Nell Merlino.

VICTORIA: Oh, I like her already.

MERLINO: It was not a given that we could run companies or be on the Supreme Court or any of that.

COLLEEN: Nell is perhaps best known for...

MERLINO: ...the creation of Take Your Daughters to Work Day with Gloria Steinem at the Ms. Foundation in the 1990s.

COLLEEN: I first interviewed Nell years ago back when I was a business reporter at Dow Jones...

COLLEEN (FROM ZOOM): ...around 2005, which I think is around when I met you, because I think that's when you were probably —

MERLINO: Make Mine a Million. Absolutely.

COLLEEN: Nell created a long-running program called Make Mine a Million Dollar Business...

MERLINO: ...which challenged women with microbusinesses to grow them to million dollar enterprises.

SOT: MERLINO RINGING BELL AT NEW YORK STOCK EXCHANGE

COLLEEN: That's Nell, ringing the opening bell at the New York Stock Exchange in 2011.

VICTORIA: If you could see a video of this, you'd see a sign behind Nell that reads, “Women-Owned Businesses — Creating Jobs — Fueling the Economy.”

MERLINO: A lot of these businesses started at home. They were opportunities to increase your freedom and to set your own boundaries, as opposed to constantly trying to fit yourself into a model that was never designed for women — and particularly not designed for women who were caring for children or parents.

COLLEEN (FROM ZOOM): You're talking about the corporate model.

MERLINO: The corporate model, or the factory model.

COLLEEN: So Nell has seen women take control of their lives — and their finances — by starting their own businesses — often home-based businesses.

MERLINO: We are so reminded of it again with everybody at home working, cooking, everything; everything is happening in the house. But it is what drove a lot of women to start businesses, because at least everything was in one place, which was the house.

COLLEEN: Of course, to start your own business — well, really to grow it — you need capital.

VICTORIA: Like a line of credit or a bank loan.

COLLEEN: Exactly. And for women — and this is hard for me to wrap my head around — even in the 1970s it was impossible for women to get a credit card in their own names...which leads us to the Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974.

MERLINO: That was national, that was Lindy Boggs. I want to say Bella was on there...

VICTORIA: ...Bella Abzug, a Congresswoman from New York, sponsored the bill.

COLLEEN: The story — and it's a good one — is that Lindy Boggs, who filled her husband's seat in the House of Representatives after he died in a plane crash, had sort of this genteel Southern charm.

VICTORIA: She was from Louisiana.

COLLEEN: And when the House Banking Committee was considering a version of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, which would make it illegal for creditors to discriminate based on race and other factors, she noticed that “sex or marital status” wasn't included. So she hand-wrote it in, and gently suggested that the omission “must have been an oversight.”

VICTORIA: It passed — and President Gerald Ford signed the bill into law.

COLLEEN: Around that time, the National Association of Women Business Owners — or NAWBO — formed and began lobbying around a new cause.

MERLINO: There were logical progressions in this whole movement. They then move on to do H.R.5050, in 1980 or '88.

VICTORIA: And this was a big one. H.R.5050 was also called the Women's Business Ownership Act.

COLLEEN: It eliminated state laws requiring women business owners to have their husband or any male relative cosign a bank loan.

VICTORIA: A witness during the H.R.5050 hearings testified that she didn't have a husband, brother or living father available, so she had to have her 17-year-old son cosign the loan, because in the eyes of the government HE was more responsible by virtue of being male. I mean, this was the 1980s!

COLLEEN: NAWBO has called H.R.5050 the “big bang” of women's entrepreneurship.

COLLEEN (FROM ZOOM): And I wanted to ask if you agree with that — is that how you viewed it? How significant was it?

MERLINO: I think it's significant in that women, they were now being included in conversations that we had not been before. I think it was — I think a lot of it was cosmetic, but what we know now is all the research about: if you can see yourself — if you can see it, you can be it. I think that was incredibly important in terms of the recognition. Think about this time, this is when Sandra Day O'Connor pops up. You were starting to see this inevitable — I'm going to call it appreciation for the expanded role that women were playing in everything.

COLLEEN: Since that legislation passed, it's probably no coincidence that the number of women-owned businesses has grown at incredible speed.

VICTORIA: The most recent estimate, pre-Corona, is that there are almost 12 million firms owned by women.

COLLEEN: That's about one-third of all U.S. small businesses. Though we should note here — while there has been this progress — the very issue that Nell set out to address a few years back, about women entrepreneurs not making as much in revenue as men, is still an issue. If you zoom in on million-dollar businesses in the U.S. — if you take a look at say, five of them — only one would be owned by a woman.

VICTORIA: So — and I ask this as a millennial, who has always seen women working, and success stories like Arianna Huffington or Tory Burch — why is this still an issue?

COLLEEN: Well, part of it is that we're just starting to see a proliferation of role models for young women to emulate. That wasn't there for previous generations — maybe there was Oprah, we all love Oprah — but there simply weren't very many super-successful women in business. And then we still see issues that haven't been addressed through major legislation, that would help women — say, the government providing paid maternity or family leave.

MERLINO: I want to just pick the right words — but there continues to be this notion still of having to do everything. I think we're seeing it again writ large with what people are coping with at home at the moment. What's interesting now, though, is that fathers are being forced in the same situation because many of them can't go out either. So that has set up an interesting dynamic. But historically it was us who ended up in these situations. We don't make as much money because we have a lot to do.

COLLEEN: And then, last but not least...there is still a disturbing lack of access to capital for women business owners.

MERLINO: The boys — not all of them, but most of them — still lend to each other.

COLLEEN: Today — perhaps a little differently than 30 years ago — we see this most painfully in the venture capital arena. So we're talking high-growth startups. There's about $100 billion dollars in VC given out each year — only 2-3% goes to women-led teams.

VICTORIA: So that probably impacts women in tech the most.

COLLEEN: That's right. But I asked Nell about this, as I know that lack of access to capital can hamper the growth of women-owned business across a broad swath of industries — and that directly affects women's ability to control wealth. She once told the New York Times that women's economic independence “is the missing piece in the evolution of equal rights.”

COLLEEN (FROM ZOOM): Can you tell me what you meant by that?

MERLINO: Literally that we are not in the same rooms still when the big contracts are being whacked up. I would be very curious with the trillion dollars in stimulus, how much went to women owned companies, how much went into the hands of women at a level that would refinance or help them pivot businesses? We still see the old boys network come up in situations like that. Even though Nancy Pelosi is deciding on it, systemically, we haven't gone far enough in terms of making sure that women are in the places where the money's being doled out.

COLLEEN: So let's close this episode out on a positive note...

SUE: ...by looking at some other “firsts” that women achieved in the latter part of the 20th century.

VICTORIA: There's Sandra Day O’Connor, who becomes the first female Supreme Court Justice in 1981.

SUE: Geraldine Ferraro becomes the first female vice-presidential nominee for a major political party in 1984.

VICTORIA: Janet Reno — the first female Attorney General in 1993.

COLLEEN: Madeline Albright — the first female Secretary of State in 1997.

SUE: But it wasn’t until this millenium that a woman would reach the highest position of political power yet — spoiler alert, it wasn't Hillary Clinton.

VICTORIA: It was Nancy Pelosi, who in 2007 became the first female speaker of the House of Representatives. Meaning she’s the most powerful individual in Congress, and after the Vice President, she’s next in line for the presidency.

COLLEEN: Looking at these dates — I mean they’re all so recent — I asked Nell Merlino...

COLLEEN (FROM ZOOM): When you say the pace, do you think it's moving quickly or at a snail's pace?

MERLINO: I think it's both. My grandmothers were the first women in my family to vote. And the difference between my life and theirs is just unbelievable in terms of my health, my wealth, my mobility — mobility both in terms of revenue, but also all the places I've been around the world. What has happened? The opportunities that have been afforded women over the past 100 years are staggering. It's being able to step back and see both how long it takes and how quickly some things turnover.

MUSIC: Madame Gandhi, “The Future is Female”

WARE: I think whatever politically active women are doing today is really standing on the shoulders of the suffragists.

VICTORIA: Here's Susan Ware again.

WARE: And yet, a lot has changed. As a historian, what's been so rewarding for me is telling these stories of what women have contributed, and then trying to share them so that people today, they know that they're not the first women to have tried this, and that there are lessons that can be learned — good and bad lessons — but that they're part of a larger history. And I find it a very empowering history, thinking about being part of this larger trajectory.

COLLEEN: Vic, I know you got a little emotional during that interview.

WARE: Don't start crying! (laughter)

VICTORIA: I did. Because there’s something quite moving about situating yourself in this grand narrative of women’s history. Understanding that your life experience is shaped by the efforts of the women who came before you — women who fought for every privilege and right that you have. Women you will never know, but who have changed your life.

MUSIC: Madame Gandhi, “The Future is Female”

COLLEEN: Next week in the final episode of this special series...

SUE: ...we take a look at the women who are taking up the mantle.

ALEXANDRIA OCASIO-CORTEZ: Hello Bronx and Queens, my name is Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

VICTORIA: A new generation of women taking us into the future.

MUSIC: Madame Gandhi, “The Future is Female”

OUTRO: This has been a special project from The Story Exchange, a nonprofit media company that provides inspiration and information for women entrepreneurs. If you liked this podcast, please share on social media or post a review on iTunes. It helps other people find the show. And visit our website at TheStoryExchange.org, where you’ll find news, videos and tips for women business owners. And we’d love to hear from you! Drop us a line at [email protected] — or find us on Facebook. I'm Colleen DeBaise. This episode was produced and reported by Victoria Flexner and myself. Sound editing provided by Christina Kelly and Nusha Balyan. Archival research done by Noël Flego. Special thanks to our voice over talent: Kathleen Murphy. Our mixer is Pat Donohue at String & Can. Executive producers are Sue Williams and Victoria Wang. Our thanks to Madame Gandhi for so generously allowing us to use “The Future is Female” as our theme song. The song “Near Light,” performed by Ólafur Arnalds, is courtesy of Erased Tapes Records and Kobalt Songs Music Publishing. Archival clips come from the New York City Municipal Archives, Creative Commons and the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library.