It’s Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, a time to recognize the contributions AAPI people have made to our country through politics, science, business, sports, activism, art, and of course, literature.

In that spirit, we’ve curated a list of seven books authored by AAPI women, all of whom have a different relationship with their culture and identity. Whether fiction or nonfiction, all contain courageous testimonies of trauma and healing.

Keep reading to learn more about these books – each one a love letter to its author’s culture.

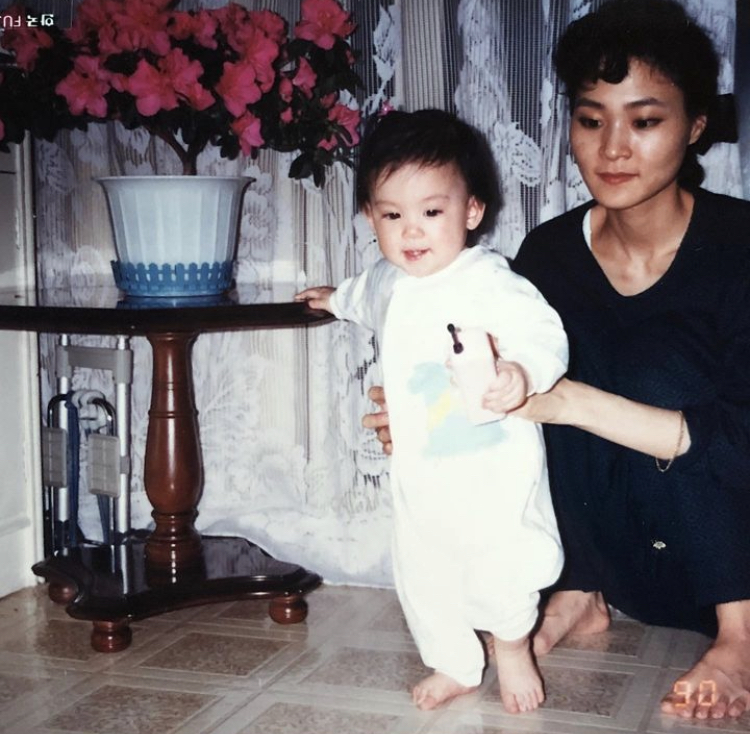

Crying in H Mart by Michelle Zauner

Many know Michelle Zauner by her indie rock persona, Japanese Breakfast. But with the 2021 release of her memoir, which topped the New York Times Bestseller List, she became a literary sensation. Complete with family photos, the memoir chronicles her experience growing up as one of the few Asian-American students at her school in Oregon, trying to balance her mother’s high expectations of her with her desire to fit in. After moving to the East Coast for college, she drifts further and further away from her Korean identity – until her mother is diagnosed with terminal cancer. It’s through this traumatic experience that Zauner begins to reconnect with her roots through food, history and language, all out of desperation to stay connected to her mother.

A Place for Us by Fatima Farheen Mirza

An Indian wedding gathers a family back together – including estranged son, Amar, who is making an appearance for the first time in three years to take his place as brother of the bride. The reunion of this once close-knit family raises lots of memories of secrets and betrayals, but also raises a question of whether they can fix everything that’s broken. The story takes us back to the very beginning of this family’s life, when parents Rafiq and Layla first arrive in America from India. As their three children grow up, they struggle to find a balance between the two cultures, which puts a strain on their family that only deepens with time. A Place for Us is an ode to today’s American families, especially those that are split between two different cultures.

Good Talk by Mira Jacob

Are white people afraid of brown people?

Can Indians be racist?

What does real love between really different people look like?

These are all questions Mira Jacob’s six-year-old son has asked her, as he tries to understand his half-Jewish half-Indian identity. What started as a successful Buzzfeed article “37 Difficult Questions from My Mixed-Raced Son,” evolved into a full-fledged graphic memoir in which Jacob looks back on her own journey as a first-generation American in order to find the answers to her son’s questions. Using humor, she reflects on everything from uncomfortable relationship advice from her parents – who came to the United States from India one month into their arranged marriage – to the imaginary therapy sessions she has with celebrities like Bill Murray and Madonna. She also remembers what it felt like to be a brown-skinned New Yorker after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. In doing so, she finds a way to have these hard conversations with her son.

The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan

It’s 1949. Four women, who have recently fled from worn-torn China to San Francisco, begin having regular meetings to eat dim sum, play mahjong and bond with one another. All of them have their own struggles – including very Americanized daughters they try to stay close to, but who are slowly drifting away. Calling themselves the “Joy Luck Club,” they help each other cope with unspeakable loss by sharing stories and trying to untangle the generational and cultural conflicts they face with their daughters. This support system they’ve built gives them courage as they face the daily challenges of life as immigrants. Amy Tan’s New York Times bestselling novel, originally published in 1989 and turned into a 1993 movie, is still beloved for its exploration of the unbreakable bond between mothers and daughters, and even between mothers and other mothers.

Know My Name by Chanel Miller

Chanel Miller was first known to the world as “Emily Doe,” the anonymous victim of the Stanford Assault Case of 2015. Before the #MeToo movement took off, Miller’s letter to her attacker, Brock Turner, sparked nationwide conversations about power structures and rape culture. In Know My Name, she sheds her “Emily Doe” alias and reclaims her own story. By describing her trauma and feelings of isolation, she sheds light on the very real problem of victim blaming. Miller’s “coming out” as Asian-American was important to many Asian-American women because her reflections on upbringing, identity, trauma and healing help to break down the stigma and the “invisible” feeling many Asian-American survivors are familiar with. Her account of how she was treated by the legal system unveils the systemic bias that makes it difficult for minority women to find justice.

This Is Paradise by Kristiana Kahakauwila

In this book of stories, Kristiana Kahakauwila travels the islands of Hawaii and explores the space between the postcard Hawaii that attracts tourists and the true Hawaii that only locals know. She tells stories of real Hawaiian people caught in the tides of tradition and expectation as they claim identities for themselves. In “The Old Paniolo Way,” a patriarch tries to settle the affairs of his farm before his death. In “Wanle,” a beautiful and tough young woman wants nothing more than to follow in her father’s footsteps as a legendary cockfighter. All Kahakauwila’s stories, which span across the islands of Maui, Oahu, Kauai and the Big Island, paint a picture of a frequently romanticized place inhabited by people who all share a powerful desire to belong somewhere and truly feel at home.

A Tale for the Time Being by Ruth Ozeki

Ruth is a novelist living on a remote island in Canada with her husband. One day, while walking along the beach, she finds a Hello Kitty lunchbox washed ashore – and it’s full of artifacts Ruth believes could possibly be debris from Japan’s 2011 tsunami. By further investigating the contents of the lunchbox, she is pulled into the story and unknown fate of its owner – a 16-year-old girl from Tokyo named Nao. Depressed and isolated from her peers, Nao is contemplating suicide, or “dropping out of time,” as she calls it. Before doing so, she first plans to document the life of her great grandmother, a Buddhist nun who’s lived more than a century. Through the relationship between writer and reader, and past and present, Ozeki tells a powerful story about the universal search for home.