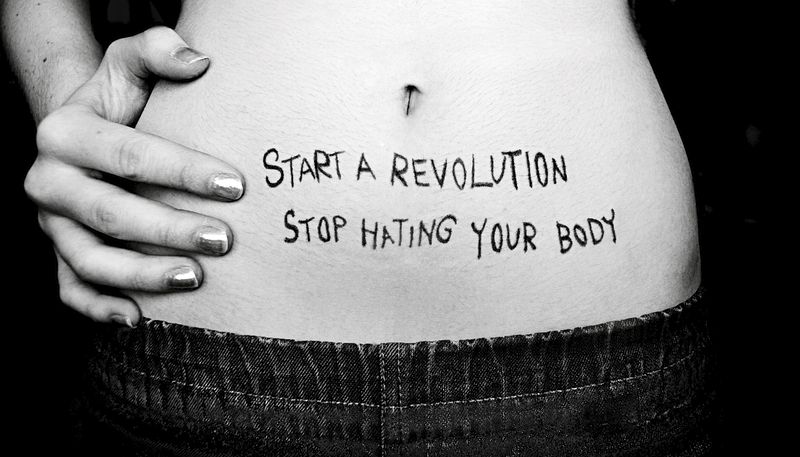

“Embrace your curves.” “Celebrate your body!” “Love the skin you’re in.”

You’ve likely seen some iteration of these missives while shopping or scrolling through your ad-ridden social media feeds. The tag lines are broadly worded, blandly positive, and usually evoked to sell plus-size clothing, or vitamin supplements, or body lotions – usually to women.

But an increasingly loud chorus of voices say these catchphrases – deployed in service of so-called “body positivity” – have turned a movement formed to fight for equal rights for plus-size people into nothing more than a marketing ploy. Some liken it to “greenwashing,” a practice in which a company purports to be environmentally responsible for appearance’s sake but isn’t actually enacting sustainable practices.

And the use of terms like “embrace” in these “body-positive” ads – while on the surface a positive sentiment – have diluted the real message that longtime propoponets have fought to elevate: that weight discrimination still happens, every day, no matter how you personally feel about your curves or your waistline.

Body positivity is “not about individual self esteem,” says Tigress Osborn, chair of the National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance. “It’s about equal access and equal rights in the culture” for people who “still go out the door and face real, practical, life-altering discrimination.”

From Good Fight to Sales Tactic

While rumblings of it actually began well over a century ago, body positivity first took form as a movement in the 1960s.

Like feminism, body positivity has experienced waves and shifts, often moving in step with larger social trends. At its start, advocates sought to first bring public attention to systemic biases that harm fat individuals. By the 1990s, a second wave emerged, pushing back against diet culture and disordered eating in pursuit of weight loss. The advent of social media sparked a wave all its own, as images of unrealistic beauty standards received new levels of saturation.

Today, proponents of fat acceptance still want the world to be an equitable place for people of all sizes – just not in the way modern-day advertisers and influencers mean it. Plus-size people should “have the same access to everything,” says educator and activist Bryan Guffey. “We want systemic barriers to be removed.”

At present, stigmas and stereotypes against fat individuals still impact every facet of life, researchers have found – from doctor visits, where any and all problems are attributed to a patient’s weight (often with catastrophic results), to dinners out, where larger customers struggle to find comfortable places to enjoy a meal.

That’s why inclusion in ads – something that’s been on the uptick since about 2017 – is hardly a priority, and certainly not a defining trait of the movement. Not that increased visual exposure doesn’t have its potential benefits, but it’s only one part of the equation, activists say.

Besides, much of the advertising that supposedly strives for inclusivity often features models who are still mostly white, with bodily proportions that adhere to a societally prescribed ideal. “That just moves us right back toward the standard we had before,” Osborn points out. When advertisers “take those already closest to the center and make them representative of marginalized people, that just pushes [more oppressed] people back.”

And in numerous cases, the products shown in supposedly empowering ads aren’t even available to fat consumers. Fashion brands like Madewell and Everlane have come under fire for featuring plus-size models they don’t actually make clothing for. One could perhaps consider that to be a step forward from the active anti-fat discrimination that was once standard practice for clothing brands like Lululemon and Abercrombie & Fitch – but it still rings hollow.

Especially when you factor in the $20 billion in buying power the plus-size population is estimated to have, as well as the trend of younger shoppers seeking out brands whose values align with their own. Through that lens, co-opting a term like “body positivity” and including the errant fat model becomes a shrewd sales tactic, rather than an effort at inclusivity.

“The trajectory has been very similar to that of other kinds of movements – from a real cause, to unfortunately becoming an opportunity to” sell to consumers, says Thomaï Serdari, adjunct marketing professor at New York University’s Leonard N. Stern School of Business.

Guffey, also co-host of the podcast “Unsolicited: Fatties Talk Back,” agrees, noting that the typical retailer is “driven, very often, by capitalism” rather than a desire to be an agent of change. “When commerce chooses to engage with something, there is inherently a limit as to the lengths it will go.”

What’s Actually At Stake

The bigger issue, advocates say, is the way in which advertisers’ use of body positivity obscures the ways in which the world actively discriminates against fat individuals – precisely what body positivity as a movement aimed to teach the world about in the first place.

And that discrimination takes place to this day – even if it sometimes wears a kinder face. Take Nithin Kamath, founder of Bangalore-based brokerage firm Zerodha, who experienced a bit of internet virality last weekend when he posted about a new challenge at his company: lose weight and we’ll dole out bonuses. “Anyone on our team with BMI [sic] less than 25 gets half a month’s salary as a bonus. The average BMI of our team is 25.3, and if we can get to less than 24 by August, everyone gets another half month as a bonus,” he tweeted.

Kamath’s heart may well have been in the right place. But as Twitter users logged in by the thousands to point out, these types of initiatives ultimately perpetuate weight discrimination, by linking fatness with badness or otherness and attempting to unite a group of people in pushing it away – which ultimately makes life actively harder for fat individuals to navigate.

It’s a workplace issue that extends well beyond the confines of Kamath’s offices. Research and anecdotal evidence have found that it’s harder for fat people to land jobs, get promoted or find community within the companies they work for, due in part to stereotypes labeling fat individuals as inherently lazy or unintelligent. And bias against fat individuals has actually slightly increased over the years.

So what’s to be done?

Legislative protection may be one solution, advocates say. At present, only one state in America – Michigan – offers employees specific protection from being fired due to height- or weight-related reasons. San Francisco and Binghamton, New York, offer such protection on a municipal level. Similar statewide bills are in the works in Massachusetts and New York.

Businesses can also proactively make a difference by making sure both plus-size employees and customers aren’t automatically excluded, Guffey adds. Owners or managers can ask: “How do we design our supply chain and our choices in products to be truly accessible to all people? What does it mean to make sure a space is truly comfortable for people of every size?”

Companies have achieved varying degrees of success in their inclusion efforts. Serdari points to personal care company Dove (with its “Real Beauty” campaign), and the various fashion and beauty properties owned by pop superstar Rihanna, as positive, outward-facing examples. Osborn and NAAFA, meanwhile, recently consulted with tech giant Google on its own fat-focused DEI initiatives.

But none of this work can happen in a vacuum, experts stress – the approach has to be intersectional. “We have to think about all of the ways people’s bodies are oppressed,” Osborn notes. “It can’t ever be a single issue or struggle.”

People of color, for instance, disproportionately suffer the effects of weight discrimination – and always have. As Guffey notes, “You cannot pull apart anti-fatness and anti-Blackness. You can’t do fat liberation without Black liberation. All of these things are intertwined.”

Doing this work matters, first and foremost, because fat individuals aren’t going anywhere – and they have rights. Says Osborn, “There have always been fat-ass, bad-ass people living their best lives, regardless of cultural beauty standards. And there will always continue to be.” ◼️