“In a way, overexposing myself has always felt like the safest option.”

Model Emily Ratajkowski wrote those words in one of several personal essays found in her New York Times best-selling memoir, “My Body” – a #MeToo missive intended to foster solidarity with other survivors. She continued in that passage: “Strip yourself naked so it seems like no one else can strip you down; hide nothing, so that no one can use your secrets to hurt you.”

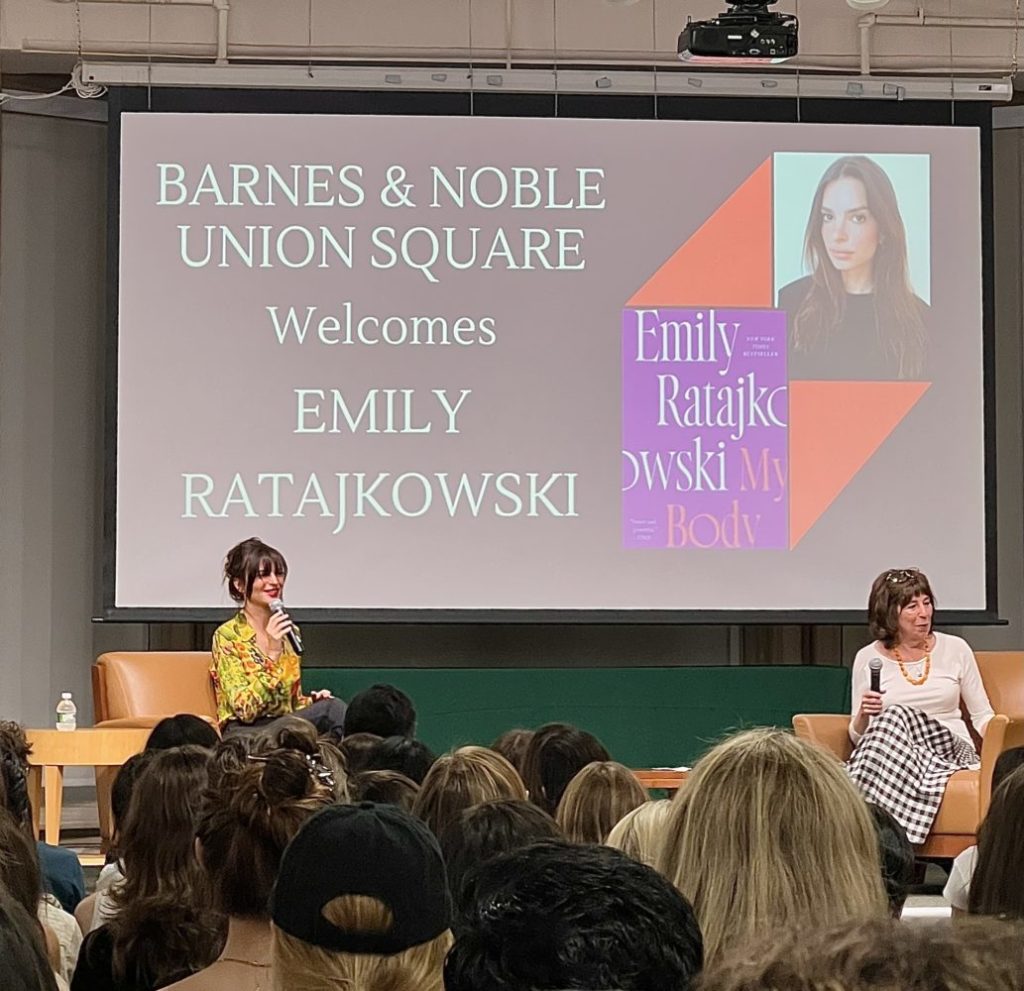

Earlier this month at a Barnes and Noble in New York City’s Union Square, Ratajkowski and her editor, Sara Bershtel, hosted a release party for the paperback version of the book. There, they shared how they have seen “My Body” create a sense of community among women who can relate to Ratajkowski – as evidenced by the crowd of roughly 100 people who gathered for the event.

The purpose of the book is to “[open] up these vulnerable conversations that don’t always happen between women, because we do feel like it’s just you and it’s not like a larger thing,” Ratajkoswki told the crowd – to inspire other women to share their previously unspoken tales, and to let them know they are not alone.

When Ratajkowski’s book was published in November 2021, it was met with mixed reviews, with some claiming passages like the one above failed to address the problem of sexual harassment in the entertainment world beyond “her own discomfort on a beach vacation.” But “those kinds of situations are still happening to me, so I know that they are definitely happening times 100 to other women,” the actress, and founder of the swimwear line Inamorata, said at the release event.

Ratajkowski recounts in her book how she was sexually assaulted numerous times throughout her life, starting at age 14 – perhaps most famously on the set of the “Blurred Lines” music video. She alleges that singer Robin Thicke came up behind her and grabbed her breasts. And during one event on the press tour for “My Body,” she recalls a male model grabbing her butt.

But she also explores the importance of celebrating or savoring moments in her body, even when it’s difficult. One essay, “Releases,” details a small yet pivotal moment from the first trimester of her pregnancy with her son. She had gone on a bike ride with her best friend and now ex-husband, and recalled contemplating all that her body was capable of – how she was carrying an entire life inside her, while also keeping herself alive. Parts of this passage were so powerful, Ratajkowski added at the event, that Valentino used it for their campaign, “The Narratives.”

Another chapter, meanwhile, explores how Ratajkowski spent most of her career dissociating herself from her body. Bershtel explained to the audience that “she was writing about something very complicated, which has to do with being a woman, being a commodity; how one participates in that, and how one is somehow captured by that.”

A 21-year-old pre-law student in attendance, who preferred not to be named, said she felt validated when reading Ratajkowski’s essays. Some of Ratajkowski’s experiences, like an assault in high school and an inability to regain control of threatening situations, resonated with the student. “I felt like I wasn’t alone,” the student said. “Like, even these beautiful women who always seem so confident and put together, they have issues that we all have to deal with as women.””

That sort of connection was Ratajkowski’s mission in publishing her journey to loving and appreciating her body. As she wrote in the last chapter of “My Body”: “‘It doesn’t matter what I look like,’ I realized. I thought again of the tiny life housed in my body. I wanted to cry out: ‘Thank you! What a joy life can be in this body.’”

This article has been updated since originally published to remove identifying details of the student quoted.