The ramp-up to the 2024 presidential election has commenced. (God help us all.)

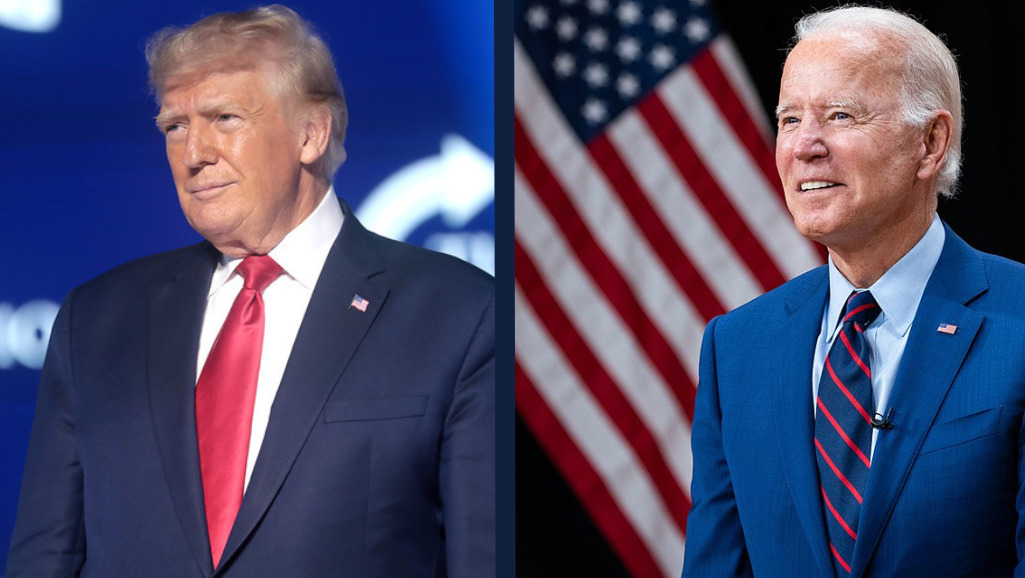

With campaign discourse already underway – especially among an eight-strong pool of Republican contenders that includes former President Donald Trump and Florida governor Ron DeSantis – candidates are making their priorities and positions known. They’re discussing almost everything, it seems, from highly contentious issues like abortion and gun control, to less sensational matters such as cryptocurrency.

Two things they aren’t mentioning? Federal paid leave and universal childcare.

And it’s unclear how likely it is for these issues to ever make it to the debate stage, says Kelly Dittmar, research director of the Center for American Women and Politics, a think tank at Rutgers University – “even though, when you ask people how important they are, many, especially parents, talk about how essential those policies are to their day-to-day wellbeing.”

Indeed, federal paid leave is especially popular with the vast majority of voters across the board. And it’s not hard to understand why – at present, the United States is one of only eight countries worldwide that doesn’t guarantee paid leave to its citizens, and the only industrialized nation that fails to do so. As a result, just 24% of private-sector workers have access to paid leave at present, with only 11 states having passed laws to offer it to their citizens.

Childcare costs, meanwhile, are near-impossible for many Americans to afford – those that can, often dedicate the majority of their monthly incomes to it. (Yet at the same time, childcare workers themselves remain woefully underpaid.)

Federal paid leave and universal childcare programs would vastly improve American lives by the millions, offering stability that would promote better mental health and overall economic security. Plus, research efforts show such programs to be a boon for employers, too.

Yet both policies remain stalled. And in the meantime, women – women of color in particular – are “so disproportionately affected by [the lack of] paid leave and childcare,” says Aprill O. Turner, vice president of communications at Higher Heights, an organization that seeks to empower Black women voters and candidates. That lack of social support for caregivers consistently forces women into rock-and-hard-place decisions around their careers and health.

For the most part, Black women voters, like many individuals throughout the U.S., are concerned with “how to keep groceries on the table,” Turner says – and those economic woes “all play together,” especially for job seekers who are traditionally excluded from ”positions that grant us the paid leave we need to take care of our families.”

A Far-Off Promised Land

Federal paid leave and universal childcare have long been Democratic talking points – enough so that one might have thought that full Democratic control of Congress during the first two years of President Joe Biden’s administration would have ensured action around them. However, opposition from Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia tanked any hopes of enacting nationwide legislation at that point in time.

That said, Biden did include paid leave and childcare in his 2023 budget. It’s largely a symbolic move, though, since House control was ceded back to Republicans in the 2022 midterm elections. Their opposition largely hinges on Democrats’ proposals to use taxpayer dollars to fund such initiatives.

In the meantime, families need help – and aren’t getting it. Citizen-led grassroots efforts such as Moms First (formerly the Marshall Plan for Moms) have cropped up to shed light on this growing problem. And earlier this month, national collaborative Paid Leave for All teamed up with Glamour magazine to host a day of advocacy around the topic in Washington, D.C. There, Rep. Rashida Tlaib of Michigan, a co-founder of the Mama’s Caucus, remembered the difficulty of birthing her second child before returning to work almost immediately.

“I had him on Thursday, and I went back to work on Tuesday,” she said. “Let’s be unapologetic about this. We are asking for what is right and moral.”

At present, the only federal legislation passed around time off is the 30-year-old Family and Medical Leave act – a critical law that guarantees up to 12 weeks for American workers to tend to their caregiving duties. But those weeks are unpaid. And, while Biden did make a direct investment in childcare in 2021 through the American Rescue Plan, which included a $24 billion childcare stabilization program, those benefits expired last fall.

With Congress deadlocked, hopes of progress are dwindling – but they’re not extinguished.

The biggest proposal presently on the table with regards to paid leave is the FAMILY Act, co-authored by Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand of New York and Rep. Rosa DeLauro, a senior Democrat from Connecticut. This law, if passed, would turn those 12 guaranteed weeks into paid time off, with workers receiving up to 66% of their typical monthly wages (with a $1,000-per-week cap).

DeLauro began drafting the FAMILY Act in 2010, ahead of its first introduction to Congress in 2013. In a statement to The Story Exchange, she called it “a matter of right and wrong.” She added: “If paid family and medical leave is good enough for members of Congress, then it is good enough for the American people.”

It was recently reintroduced for consideration, with a new, expanded definition of “family,” among other changes. And, DeLauro notes, it’s especially pressing now. “A pandemic forced many women and people of color out of their jobs,” she said. “They did not opt out of the workforce, but were forced out because of inadequate policies.”

Rep. Chrissy Houlahan of Pennsylvania’s 6th district is also in the paid-leave fray. She recently co-created the Bipartisan Paid Family Leave Working Group, a six-member cohort of Democrats and Republicans who seek to “to figure out a workable way to help more people across the U.S. gain access to paid leave,” she said in her own statement to The Story Exchange.

Houlahan previously helped pass a law granting 12 weeks of paid parental leave to U.S. service members and government employees. The next clear step, she adds, is “to ensure the same benefits for everyone else.”

In order to reach that goal, she and others agree: Voters should seek out candidates that support paid family and medical leave – both in words, and legislation.

That could mean electing more women at all levels of government – studies show a direct relationship between the presence of women lawmakers in democracies throughout the world, and the adoption of nationwide paid leave and childcare policies. At Higher Heights, Turner suggests Black women leaders, in particular, could move the needle in a positive direction. “When they come to the table, they bring our concerns – everyone’s concerns,” she says.

Either way, as the field for the Presidential campaign becomes more crowded – largely by white men – DeLauro says, “we must ensure this issue is central in conversations leading up to the 2024 election.” ◼