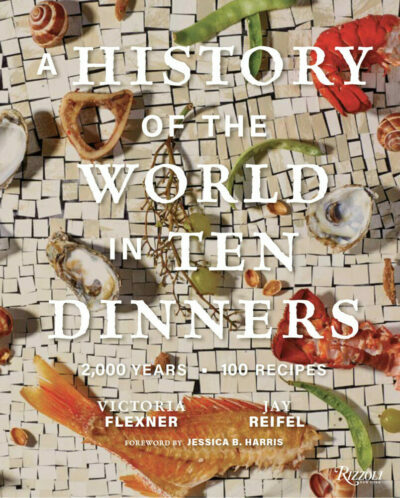

Victoria Flexner is the editor of our 1,000 Stories Project – and as of this week, author of the recently released “A History of The World in Ten Dinners” (Rizzoli). A food historian by training, Flexner founded the New York City-based historical supper club Edible History in 2014, along with chef Jay Reifel, and the two have spent nearly a decade hosting dinner parties around the city – each based in a specific era in history, with unusual dishes sourced from period manuscripts, cookbook and culinary compendiums. Their supper clubs have transported diners to the smells and tastes of Tudor King Henry VIII’s court, the streets of ancient Rome and the stops along the medieval Silk Road, among others. When the pandemic hit in March 2020, supper clubs abruptly came to a halt, presenting Flexner with a new challenge – how to keep Edible History alive in a time of Covid lockdowns. She began working on a book proposal for what would become “A History of The World in Ten Dinners” and in 2021 it was acquired by Rizzoli, an imprint of Penguin Random House. Two years, and a whole lot of research and recipe testing later, Flexner and Reifel’s book is out in the world for history buffs and homecooks to enjoy. An excerpt follows.

At each Edible History dinner there is an exciting moment when the first dish emerges from the kitchen and is placed before a guest. As the guest looks down at their plate, examining its contents, cross-consulting with the menu, and exchanging curious glances with fellow diners, I begin to tell our evening’s crowd about the dish placed before them, its history and how it relates to the time period of the night. The show begins.

Each course functions as a window into the wider historical narrative. Black chicken and peaches from Emperor Domitian’s rule are a taste of the madness that plagued the emperor who once served guests a meal dyed entirely black; perhaps the fall of Rome could have been prophesied from the dinner table. Spiced raw beef with a buttery dipping sauce from the Ethiopian Empire gives us a taste of Empress Taytu’s fondness for high quality and expensive ingredients. Cockenthrice, made in King Henry VIII’s time by sewing the front end of a pig to the back end of a capon, demonstrates the elaborate theater and trompe l’oeil style of Tudor banquet food.

The food served and the stories told at an Edible History dinner allow guests to inhabit for a moment a shared metaphysical space with someone who died hundreds of years ago – to experience the same flavors and smells that Domitian, Taytu and Henry did. This is food history. A unique kind of history, that provides deep insight into the actuality of past existence, and in turn breaks down preconceived notions and debunks popular myths.

For example, you might imagine that the Medici ate pasta with tomato sauce, or that the peasants working the lands of the Holy Roman Empire subsisted on a meager diet of potatoes. But they didn’t – because potatoes and tomatoes come from the Americas and were not introduced to Europe until after 1492. Similarly, Indian curry, Sichuanese soups and Isaan Larb did not contain a single chili pepper until the Portuguese introduced the plant to the Asian continent in the sixteenth century. The study of food can dramatically alter the way we perceive our own culinary heritages.

The study of food also shows us that we have been living in a globalized world for a very long time. International commerce and trade are not by-products of our modern global world. Spices, textiles, precious stones, animals and even people have been making their way along the Silk Road for millennia. By the thirteenth century, knights in England were sprinkling Indian pepper on their roast meat and spicing their wine with cloves from Indonesia.

And so food history reveals to us truths that exist outside traditional historiography. Your morning pastry and hot beverage of choice tell impossibly grand stories. Food speaks of whole lives lived, entire civilizations and cultures. To eat what was eaten before is, perhaps, the closest we can come to recovering the stories of those who have been largely forgotten by traditional history.

It is no secret that the history we learn today has, for the most part, been written from a Western point of view and largely by white men. The European colonization and subjugation of most of the known world starting in the 15th century produced a “World History” that begins with the Age of Exploration and moves through time linearly from the perspective of the conquerors. The result is a history that is not truly reflective of the actual experiences of most people who lived on this planet for the last 500 years.

We have missed out on so many perspectives. How do we recover these lives, these voices? How do we learn about people who left nothing behind? We write history based on what remains; but what about what does not remain? What about the smell of the early morning air as Ibn Batuta set sail from Africa for the East, the conversations had at the marketplace in medieval Cusco, a meal consumed by the women who fought in the French Revolution?

Scent and taste are incredibly powerful instruments of memory. We remember vividly those dishes made for us by loved ones: what the kitchen smelled like as it was prepared, where we sat at the table, how we felt when we consumed it. We cannot know exactly how a young immigrant coming to New York in the 19th century felt or what she thought as she disembarked from a ship and took in this new metropolis. But we can eat what she ate.

It is our hope that with these stories and these recipes, we can invite readers into the conversation of history, as they set out in their own kitchens to embark on a new kind of culinary journey. ◼

“A History of The World in Ten Dinners” is Victoria Flexner’s first book. She is a food historian and founder of Edible History. She writes, lectures and hosts historical dinners around New York City.