Editor’s Note: Elizabeth Koziol is a winner of The Story Exchange’s 2023 Women In Science Incentive Prize.

Entrepreneurs are often inspired by passion to start a business. A fitness buff might turn a love of exercise into a gym, or a coffee aficionado might start a trendy café.

In Elizabeth Koziol’s case, it was an awe of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi – a type of fungus that attaches itself to the roots of plants, providing nutrients and water that those roots could not normally obtain – that led to her startup, MycoBloom.

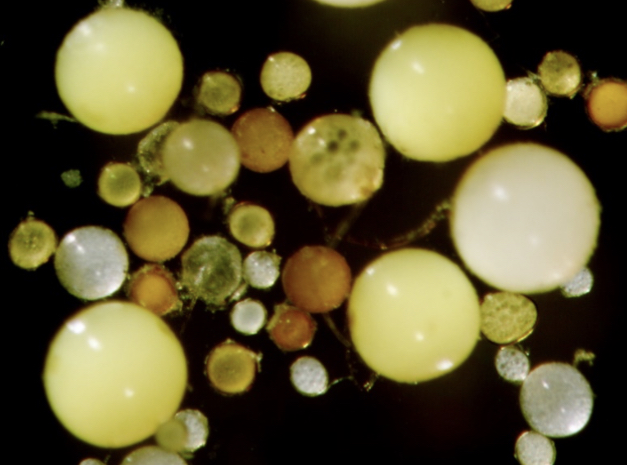

“So there’s not too many people in the world who are experts with the type of fungi that I work with, particularly because they are microscopic,” says Koziol, who is also an assistant research professor at the University of Kansas. “You can’t just go into your garden and look at your fungi.” But when you view arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, also known as AMF, under a microscope, “they’re really pretty,” she enthuses, “lots of yellows and reds and nice colors, and they’re full of fats, so they look like crystal balls. They have all these little bubbles inside of them.”

Of course, it’s not just AMF’s winsome appearance that impresses Koziol. It’s the fungi’s ability to bolster soil resilience and combat the adverse effects of human activities – such as agriculture – and the devastating impact of climate change. “Their function is acquiring nutrients, and they’re awesome at acquiring specifically inorganic phosphorus, which is the challenge for plants to get,” she says.

It’s Koziol’s expertise that makes her 7-year-old startup stand out from the competition – and a quick search on Amazon for arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi will reveal a confusing (and perhaps surprising) array of options from rivals. Koziol, who devotes most weekends and vacation days to MycoBloom, has spent two decades researching fungi in nature. A specialty is studying the country’s tallgrass prairie, much of which has been lost to farming and development. Her MycoBloom products contain only high-quality strains sourced from old-growth grasslands and forests in the U.S.

“There are these products you can buy on Amazon that have fungi from all over the world,” she says, which doesn’t support regional biodiversity or sustainability, and in some cases, the fungi in the products are already dead by the time the products are shipped. Meanwhile, Koziol cultivates her fungi on a friend’s farm in Lawrence, where she also has access to laboratory equipment for making and drying the MycoBloom products.

“Liz comes to her business as a scientist first,” says Peggy Schultz, a research specialist at KU’s Kansas Biological Survey, adding that Koziol has done a lot of “heavy lifting” in making AMF available to restorationists, gardeners and farmers. “This work is not easy in an unregulated market where arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi are the new, best thing to grow the biggest, best plants.”

Koziol’s research on prairie grasses has also shown the benefits of using AMF over fertilizer to restore soil health. Too often, fertilizer from farm fields makes its way into rivers, streams and oceans, causing even more environmental damage. “If we repair the fungal communities, we don’t have to apply as much of these fertilizers,” Koziol says.

Whether Koziol will be able to juggle her academic work and her growing business remains to be seen. “I’m a weekend warrior for my small business,” she says, “but it wouldn’t be there without my academic discoveries.” Revenue is currently about $50,000 a year, but a potential contract in the new year could easily double that and push her more into the entrepreneurship side of things. “So there’s a good sign for the future,” she says.

Meanwhile, winning a Women In Science Incentive Prize isn’t just about the grant but rather the publicity that comes with the award. “The most awesome thing [is] really people reading this story, hearing about fungi and thinking about soil microbes,” she says. “I think that would be amazing.”◼️