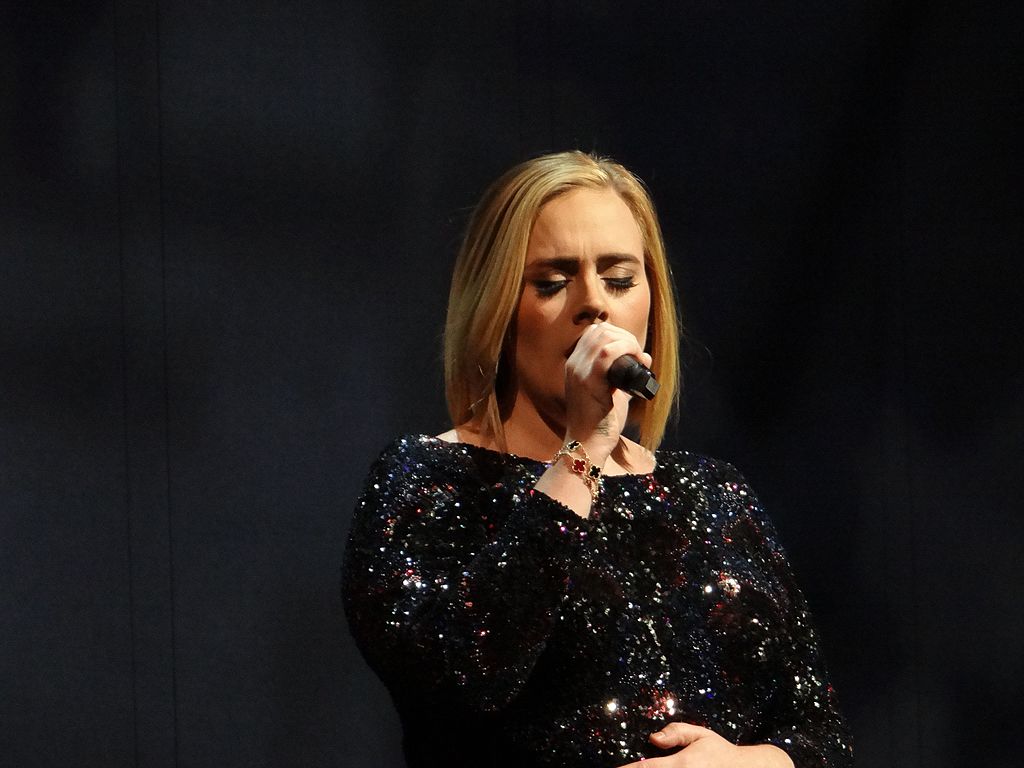

If there’s one word that has always applied to singer-songwriter Adele, it’s “stunning.”

I don’t just mean her music — though her rich, powerful voice, plaintive lyrics and lilting, soaring melodies are enough to evoke tears and stir up forgotten memories in even the most cynical of listeners. (The catharsis that comes with experiencing her work is so seemingly ubiquitous, in fact, it was even the subject of a popular “Saturday Night Live” sketch.)

But Adele is also beautiful to behold, with striking features that she plays up with her signature retro-yet-timeless makeup and fashion aesthetic. And that’s been true since she first burst onto the international music scene — which is one part of why the media coverage leading up to the release of her newest album, “30,” is so damn frustrating.

Because so much of the buzz is centered on her weight loss, instead of her craft.

When she spoke with British Vogue, Adele was crystal clear about her reasons for changing her habits — and that “it was never about losing weight.” Rather, she told the magazine, “it was always about becoming stronger, and giving myself … time every day without my phone.”

She may as well have said nothing at all about her motivations, as both publications and individuals around the world fawned once more over her smaller frame — after first doing so when she revealed her weight loss last year — and homed in on her “secrets” for dropping 100 pounds. Her frequent, cardio-centric workouts, the trainer she hired, cutting back on alcohol.

The problem isn’t her changing body, or her shifting lifestyle. The problem isn’t even about Adele — rather, it extends far beyond her, on to the beauty standards we uphold and the value calls we make on others based on how closely they adhere to those standards. To put it more directly: we prize and celebrate thinness. We automatically conflate it with health and wellness. And we do so to the detriment of ourselves, and one another.

The latest coverage of Adele is a perfect example of this. Instead of anticipating her new music, or celebrating her artistic achievements — or hell, at the very least elevating her own words about her own body — people are noting the differences in her appearance while parsing out the changes she made in her life, as though she were offering advice rather than insight.

Along those lines, actress Lena Dunham spoke to this broader point when addressing people who felt compelled to make “gnarly” comments on her weight gain, which was visible in her recent wedding photos. The cumulative implication was that she “should somehow be ashamed because my body has changed since I was last on television.” She pushed back at this idea, rhetorically asking when people will “learn to stop equating thinness with health [and] happiness,” before noting that her weight gain actually came in tandem with sobriety.

How often do we do this in our own lives — with ourselves, and with others? How often does fatphobia, or our shared fear of fatness, color our perceptions? How often do we push aside or downplay achievements while preoccupying ourselves with the bodies we work and live in? How often do our learned, engrained ideas about “good” and “bad” in the contexts of health and habits harm us, spiritually and physically?

According to researchers, quite often — stigmas surrounding weight are observed by children as young as 3 years old, and are only further reinforced as we grow older, ultimately impacting everything from employment prospects and interpersonal relationships. And yes, the situation is even worse for people of color. Perceptions regarding thinness and fatness seep quite thoroughly into our lives, even if their basis in medical fact is usually tenuous at best.

The problem then manifests itself in myriad ways. A non-celebrity example: I recently wrote about some of the worst advice women business owners had received during their entrepreneurial journeys. When Flexia Pilates founder Kaleen Canevari spoke to The Story Exchange, her input touched upon these themes. While meeting with investors about her Sacramento-based business, a hired consultant advised her to lead with her appearance as the head of a fitness brand. But “when I gained weight, I struggled with confidence, because I thought that all investors would judge my company based on what my body looked like.”

“When approaching meetings, I would stress about what to wear, which I don’t normally do, in order to hide my body,” she continued. “This feedback increased the pressure I placed on myself to be perfect. It left me feeling like I was failing all the time at everything, and that negative energy just seeped into everything.”

These themes crop up often in my life, too. What my headshot doesn’t reveal is that I’m short, and fat — a word I use because of its simplicity, and without a hint of self-deprecation. It’s hardly a stature that’s envied by others, yet I absolutely love my body. Admittedly, much of that love is tied to what my body has done and can do — from crossing dozens of finish lines, to performing in countless concerts, to creating and keeping up with my 3-year-old son — which is problematic in its own way. But I also like the way it curves and bends. I like the way it looks, the way I look.

But it took so much work, and so much unlearning, to get there. It’s been a decades-long journey through exercising (and at times, over-exercising) as a coping or defense mechanism, rather than a celebration of growing strength. Of past reliance upon diet pills that made my mind and heart race, but made pounds temporarily melt away. Of being preoccupied with everything I ate, before working past feeling like I’ve failed in some way whenever I feel full after a meal. (The last bit, I still struggle with, though thankfully less than before.)

Canevari has made it to a place of greater self love, too. “[W]hen speaking with investors, one of the conversations that has come up frequently is that, while I don’t look like a fitness model, it’s clear that I feel great in my body,” she says of today’s pitch meetings. “This has made them more interested in my company, because at the end of the day, we all want to feel good — regardless of our fitness goals.”

This is the context from which I’m taking in Adele’s latest news coverage: watching yet another person’s myriad achievements play second fiddle to focus on their evolving body; watching Adele’s enjoyment of her new lifestyle get turned into a weight loss how-to, despite her stated disinterest in losing weight; and watching our society revel in what they see — and more importantly, the meaning they’ve been taught to assign to what they see — before and above all else.

I think about the music made, the businesses launched and grown, all of the accomplishments earned, that are often only paid attention to once we’ve looked past the physical bodies of the complex human beings doing all of this work — if they’re paid attention to at all.

The point here isn’t to urge anyone toward one body “type” or another, or toward a specific lifestyle. Nor is it to endorse or put down anyone’s particular wellness goals. The point is simply to push us toward extending one another — from Adele, to Canevari, to Dunham, to me — the grace and freedom to live freely in our bodies, to feed and move them in ways that please us, without our visible dimensions defining our every experience.

Adele’s first single, “Easy On Me,” will debut later this week. My hope is simply that our shared discourse will shift to the song itself, rather than how she looks on the cover art.